Hal Hershfield, a psychologist at the UCLA Anderson School of Management, wanted to know why people weren’t saving for retirement.

Across the board, people are living longer. Logically, they’ll need more money to live comfortably in their post-work years. And yet, savings rates in the US have gone down in recent decades, not up. The average American within 15 years of retirement age saves at only one-third of the rate required to maintain their current standard of living. Why do people spend today at the expense of their future well-being?

To help explain this seemingly irrational behavior, Hershfield and his team scanned the brains of study participants while asking them to what degree various traits — like “honorable” or “funny” — applied to their current self, their future self, a current other, or a future other.

As participants answered, Hershfield’s team recorded which parts of their brains lit up.

Unsurprisingly, people’s brains were most active when thinking about their current selves and least active when thinking about a current other. (Humans tend to be a self-oriented bunch, after all.) It was in comparing these brain scans to those taken while thinking about the Future Self where things got interesting.

Hershfield’s team found that participants’ brain activity while considering their Future Selves more closely resembled brain activity while thinking about a current other rather than the current self.

Put in practical terms, when thinking of yourself in a month or a year or a decade, your brain registers that person in ways similar to how it would register Taylor Swift or the mailman or the lady driving the car in the next lane over. Understood in that way, saving for retirement is the neurological equivalent of giving money away to someone else entirely. Acting in your own self-interest (as your brain so narrowly defines it), it becomes perfectly logical to not save for retirement.

For the chronic procrastinators of the world (myself very much included), Hershfield’s findings are both comforting and horrifying. It’s definitive proof our tendency to put things off isn’t a moral failing but a neural one — our brains are wired to put our Present Selves first. (You have my blessing to use that sentence on your boss the next time you miss a deadline.)

On the other hand, the problem of working toward long-term goals feels more insurmountable than ever. We’re not just fighting our willpower (or lack thereof), but our neurological wiring.

In light of Hershfield’s study and others like it, I wanted to answer one simple question: Is it possible to make our Present Selves give a damn about our Future Selves? The answers I found were anything but simple.

What is Present Bias and how does it impact our choices?

Present Bias describes people's tendency to opt for a smaller, immediate reward rather than waiting for a bigger reward in the future. This cognitive bias explains many of our self-defeating actions — like choosing to watch Netflix rather than go to the gym, checking Twitter rather than writing that article due tomorrow, or agreeing to take on a future project that you have absolutely no time for because it's easier to just say yes.

We get to enjoy the very concrete, immediate benefits of our actions while "someone else" (our Future Selves) suffer the hypothetical, future consequences. As a result, the decisions we make for our Present Selves often look very different from our decisions for our Future Selves.

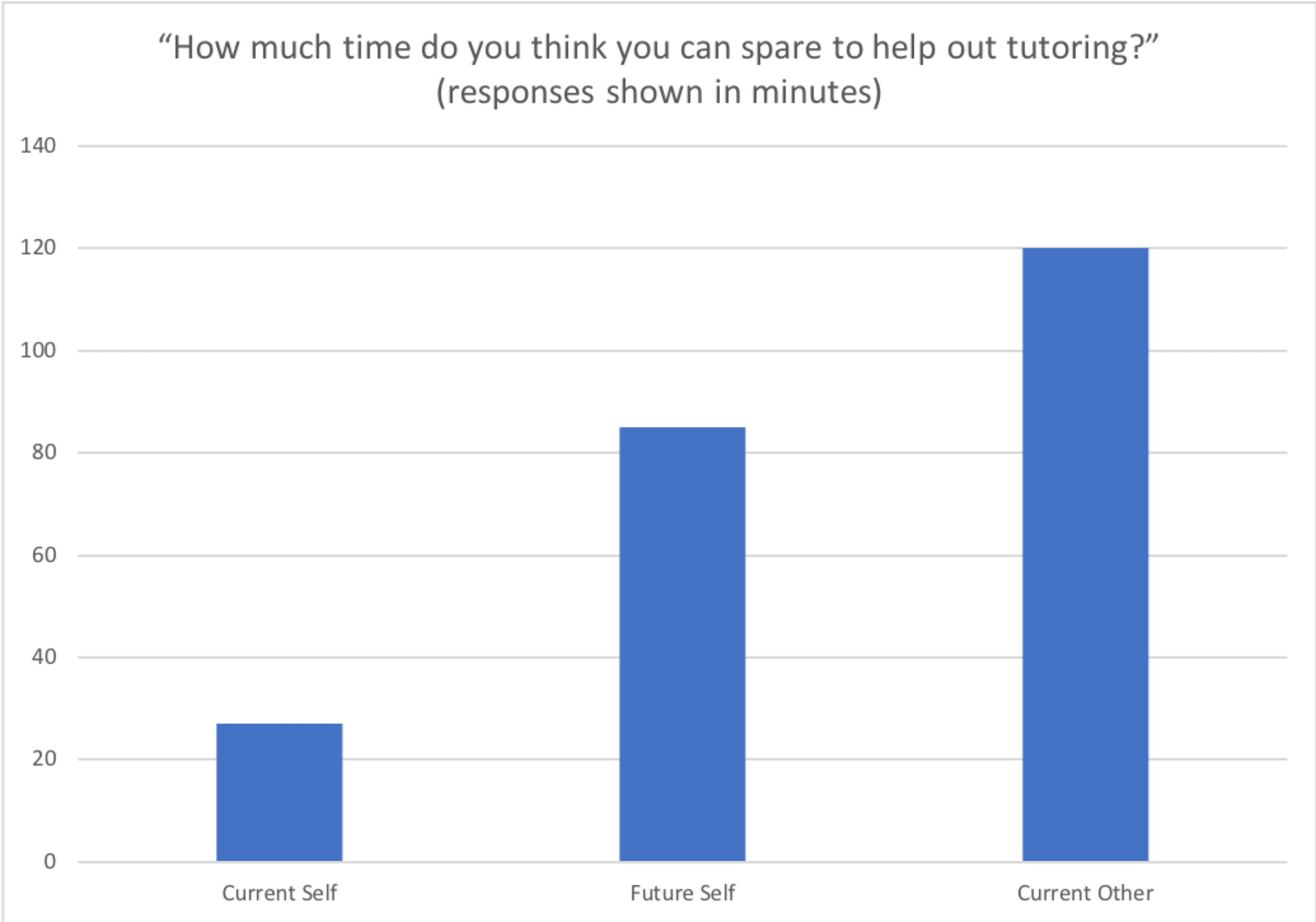

First, we tend to overcommit our future time. A 2008 paper with the apt title “Do Unto Future Selves as You Would Do Unto Others” describes one study in which undergraduate students were asked to commit their time to tutor struggling peers during mid-terms week, a particularly stressful time of year.

One group of participants was asked to commit to tutoring during the current midterm period (the Present Self condition); a second group was asked to commit to tutoring during the next midterm period (the Future Self condition); and a third group was asked how much time they thought new, incoming freshmen could spare to help out (the Present Other condition).

The researchers found a significant difference in generosity between the present and the future. Those asked how much time they would be willing to commit in the present said just 27 minutes on average while those asked to commit during the following midterm period responded with an average of 85 minutes. Even more compelling is the fact that the study found no statistically significant difference between the number of minutes students committed for their future selves and time committed for someone else entirely.

This situation may sound familiar. When was the last time you committed to taking on something new despite an already overloaded schedule? Maybe you were motivated by the excitement of a new challenge at work or the social pressure to volunteer at your kid’s school. Whatever the case, implicit in your decision was the assumption that your Future Self’s capacity and motivation would somehow be greater than those of your Present Self.

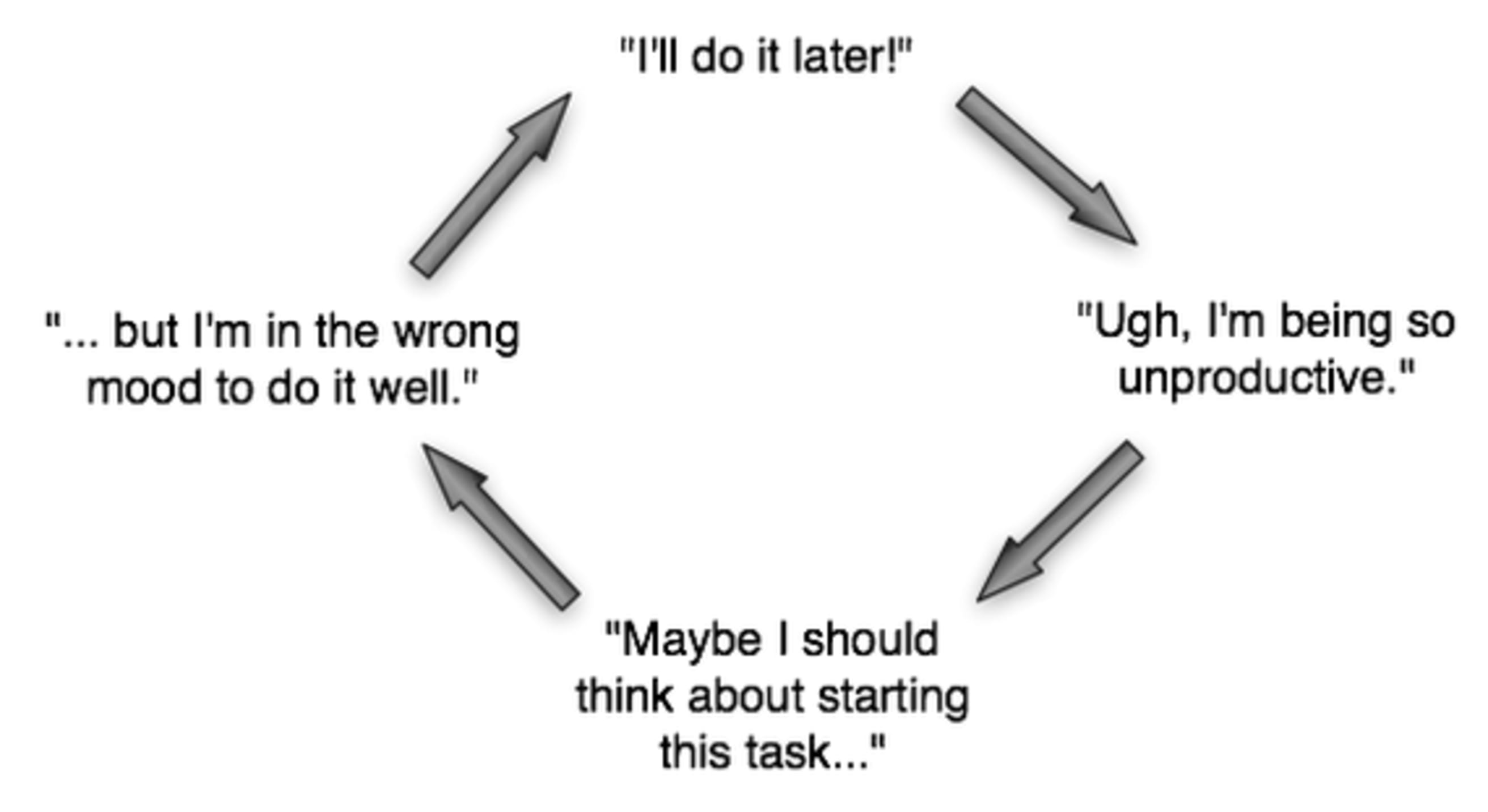

Then when it comes time to actually do the thing we committed ourselves to, we once again prioritize our present comfort over future well-being. When thinking of tasks that need to be done, we often create narratives about how difficult or painful or boring these tasks will be.

We believe that tomorrow will be different. We believe that we will be different tomorrow; but in doing so, we prioritize our current mood over the consequences of our inaction for the future self.

— Procrastination and the Priority of Short-Term Mood Regulation: Consequences for Future Self

These negative thoughts create very real psychological — and sometimes physical — discomfort. We’ve willed stress, anxiety, and fear of failure into existence. In the process, we create what author Steven Pressfield has named Resistance (with a capital R).

When faced with that Resistance, we detour. As Pressfield says in his book The War of Art:

This process of giving in and putting off is, at its core, a way to self-medicate. By transferring the discomfort of the Present Self onto the abstract and distant image of our Future Self, we’re able to alleviate the pressure of doing whatever it is we don’t want to do. We feel immediate relief.

Of course, the Future Self inevitably becomes the Present Self, and we are left to deal with what we avoided in the past as well as our feelings of shame, guilt, and worry. We overcommit and then procrastinate on our commitments. Then we punish ourselves for this procrastination, creating further negative feelings around the next tasks before us. So begins the cycle of increasingly negative emotions and further procrastination.

So how do we counteract Present Bias to achieve our long-term goals?

Understanding procrastination through the lens of Present Bias, we’re left with 3 possible solutions:

1. Force your Future Self to do whatever it is your Present Self doesn’t want to do.

In the psychological warfare between your Present Self and your Future Self, your Present Self has a couple of key advantages.

First, you can be fairly confident that your Future Self will think and act in the same exact way that your Present Self thinks and acts. That means you have full knowledge of your Future Self’s weaknesses and can anticipate your Future Self’s actions and counteractions with reasonably high accuracy.

(Of course, this will require you stop deluding your Present Self that your Future Self will somehow magically have all the willpower and motivation in the world to do whatever it is your Present Self is putting off. You won’t. Assume the worst of your Future Self and you’ll be much better prepared.)

Second, your Present Self can do any number of things to make your Future Self’s life easier. Or harder depending on how you look at it. And until time travel is invented, your Future Self can’t do a thing to stop you.

Make it easy for your Future Self to do whatever it is your Present Self doesn’t want to do:

- If you want to save more money, set up automatic withdrawals from your bank account every month so your Future Self doesn’t have the cash on hand to go blow it on whatever it is your Future Self blows money on.

- If you want to eat healthier, keep healthy snacks within arm’s reach at all times. Prep healthy meals for the week on Sunday. Freeze healthy meals to fall back on in emergencies.

- If you want to get started on whatever big project you’ve been putting off, get everything in place the night before. For example, tomorrow morning I really want to finish writing this article, so before I go to bed I’m going to close out all my other apps and put the document in full-screen mode so it’s the first and only thing I see when I open my computer.

Clearly, these strategies are not Future-You-Proof. I can, and have, immediately minimized my full-screen document in the morning in favor of catching up on Twitter. That’s why it’s handy to keep some deterrence tactics in your arsenal as well.

Make it as inconvenient as possible for your Future Self to do the things your Present Self wants to do:

- If you often sit down at your computer to make progress on a project, only to find yourself on Facebook or Reddit moments later, install apps like Freedom to block — or at least limit your time on — the most distracting sites.

- If you want to start your day with a workout but have a hard time actually getting yourself out of bed, use one of those sadistic alarm clock apps that makes you do math problems or get up and scan a barcode far away from the tempting comfort of your bed.

- If you want to save more money but fall prey to online advertising, unsubscribe from any promo email lists that you find tempting and block the sites you like to buy from.

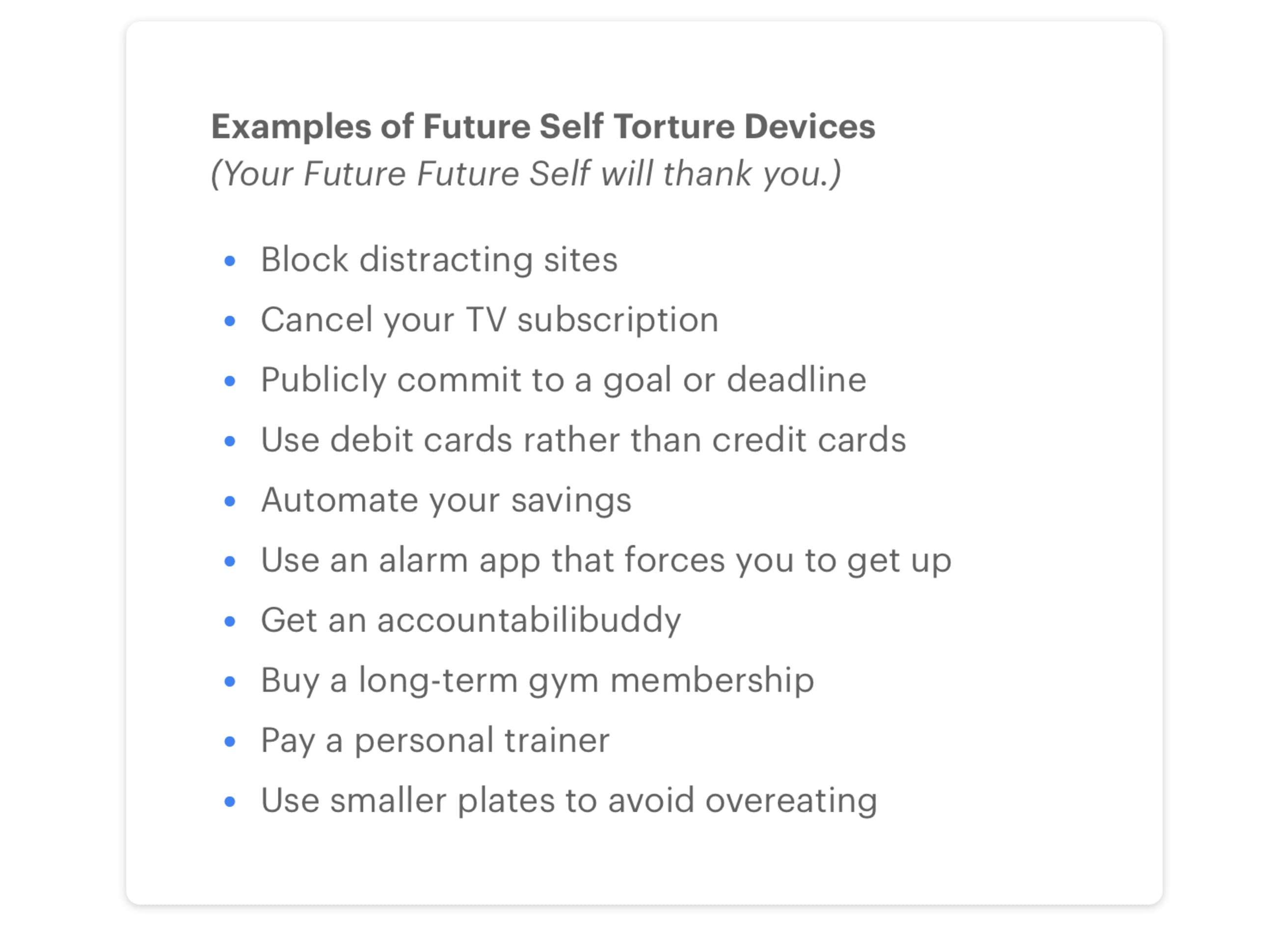

So far we’ve talked about things that nudge your Future Self toward the right path and away from the wrong one, but sometimes more drastic measures are needed — something that really forces your Future Self to stop avoiding and get to work. Some people call these “Commitment Devices”. I like to think of them as “Future Self Torture Devices”. Pot-a-to, pot-ah-to.

Here are two of the most effective ways to make your Future Self’s life miserable (your Future Future Self will thank you):

- Nothing will get your Future Self moving like a good old-fashioned deadline. When circumstances don’t create them for you, you have to create them yourself — preferably attached to some unsavory consequences if you don’t meet them.

- Get an accountabilibuddy, join a class, or hire a coach — the sunk cost combined with social pressure to follow through can make it hard to justify not showing up even when you don’t feel like it.

The specific tactics you use to set your Future Self up for better choices will depend on your unique goals. The important thing is to remember that your Future Self is going to do everything in her power to not do whatever it is that you want her to do, so you’ll need to be both creative and ruthless.

2. Convince your Present Self that your Future Self is, in fact, still You.

If the central problem is that we think of our Future Selves as other people — people we clearly don’t mind screwing over — it follows that trying to identify more closely with our Future Selves will encourage us to make better long-term decisions.

In a follow up to his 2009 neuroimaging study, Hershfield wanted to explore ways to bridge the disconnect between the present and future selves and encourage people to save more for retirement. He and his team took photos of study participants, then used image processing to visually age their faces. Participants were then placed in a virtual reality setting where they could look into a mirror and see their aged selves looking back at them. Participants who saw their aged selves said they would save 30% more of their salary for retirement than the control group.

You can actually replicate Hershfield’s experimental conditions using a (mildly terrifying) app called Aging Booth, but there are much easier alternatives to make your Future Self feel more like, well, you.

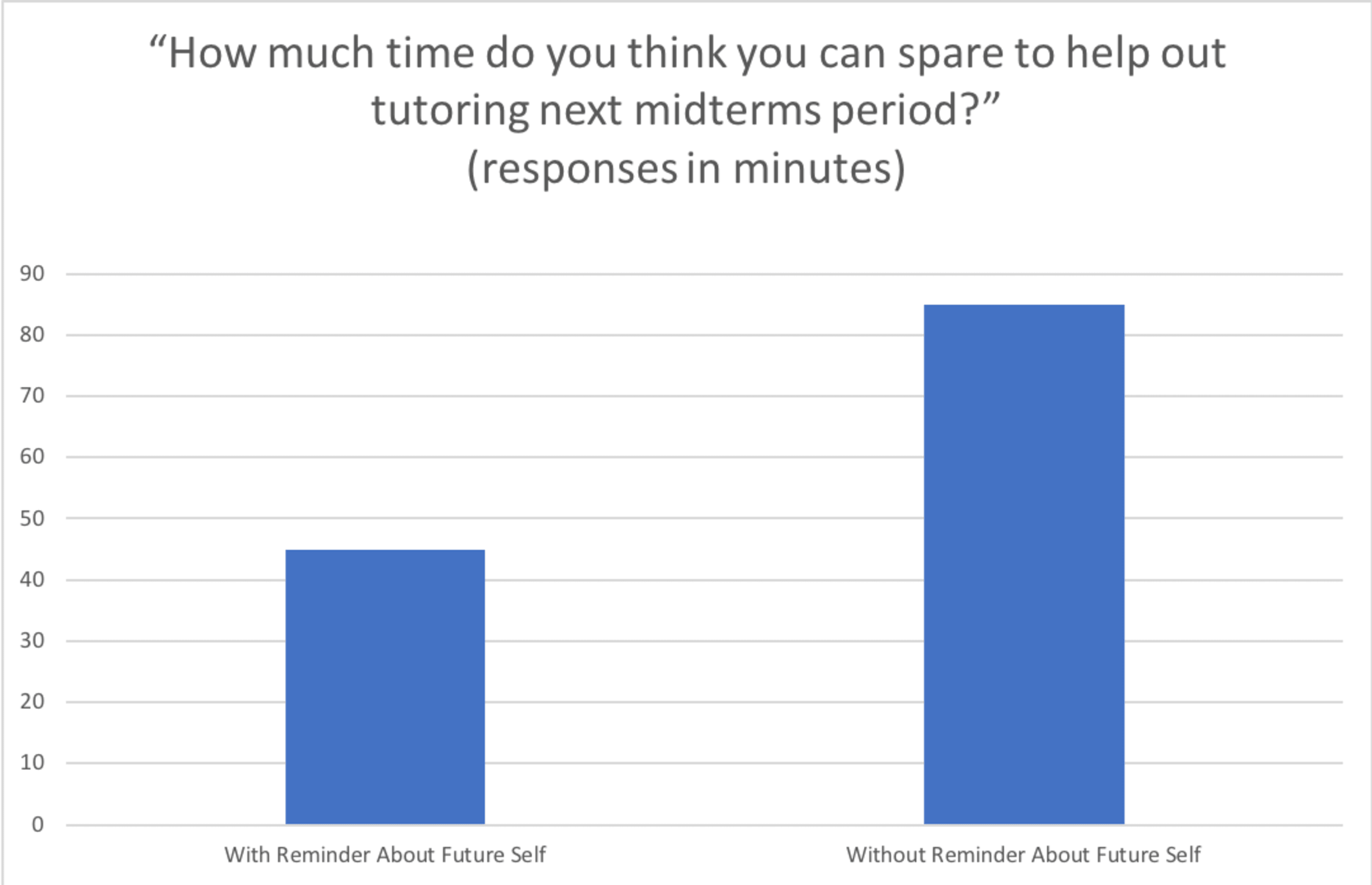

In the tutoring study described in an earlier section, a fourth experimental group was also asked to commit their Future Selves to tutor during the following midterms period. However, this group was explicitly reminded that during the next midterms they would likely have the same workload, experience the same pressures, and otherwise be the same person they are right now. Students who received the reminder committed their Future Selves to significantly fewer minutes of tutoring (an average of 45 minutes) than those who didn’t receive the reminder (an average of 85 minutes).

The results suggest that simply taking a moment to remember that your Future Self is, in fact, still you can help you make better long-term decisions.

One way to more vividly step into the shoes of your Future Self, so to speak, is to write a letter to or from your Future Self. A study published earlier this year by Hershfield along with several collaborators found that people who wrote a letter to themselves 20 years into the future were more likely to exercise in the following days compared to a group who wrote to themselves just 3 months into the future.

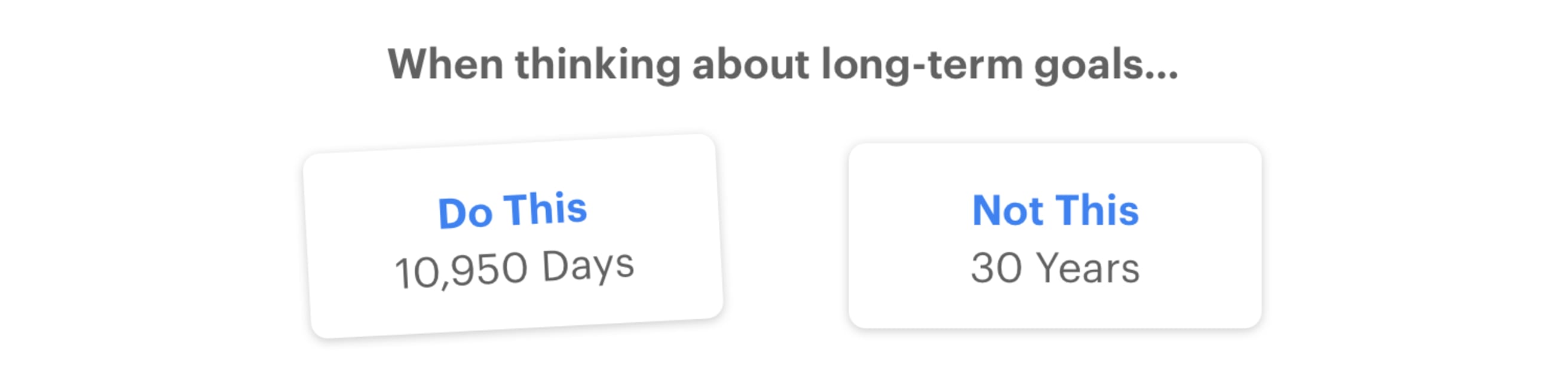

Another tactic to bridge the divide between your Present and Future Selves is to make the future seem closer. A study conducted by researchers at the University of Michigan and the University of Southern California found that when people think about future events in terms of days rather than years, the events feel like they’re happening sooner. Furthermore, when people were asked to consider a far-off event like retirement, those who were told it was happening in 10,950 days started saving four times sooner than those who were told it would happen in 30 years.

Whatever your long-term goals may be — getting in better shape, launching your own business, writing a book — thinking about your deadline in terms of days rather than months or years can help you wrap your mind around how close the future really is.

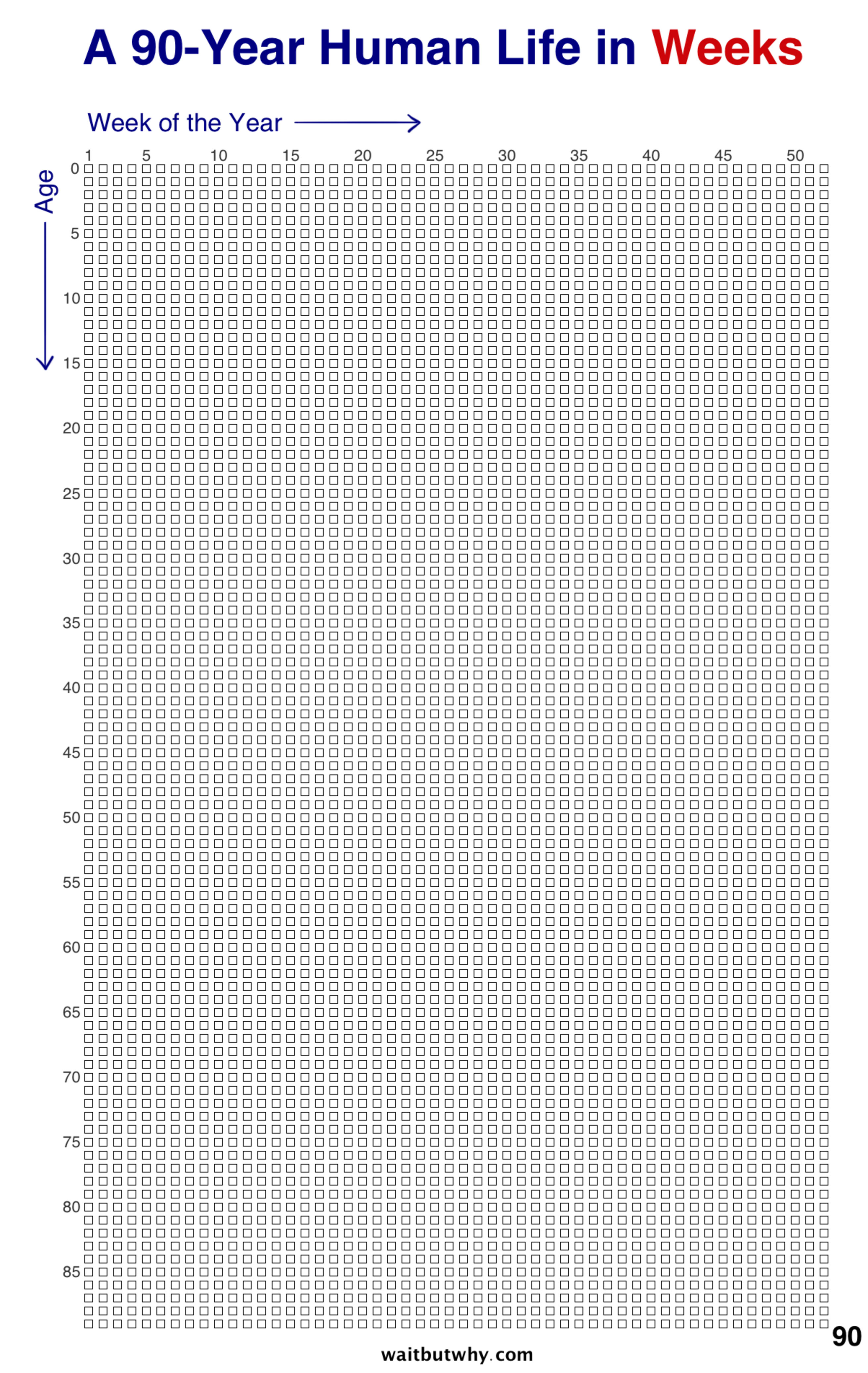

Tim Urban, writer and founder of the ever-entertaining blog Wait But Why, took this concept a step further, devising a simple yet highly effective way to visualize just how finite life can be. In an article titled Your Life in Weeks, Urban lays out a 90-year life in a grid with each row representing a year and each block representing one week. (You can buy a 24” by 36” poster version on his site for $20.) He encourages his readers to use their life grids as a tool for self-reflection and goal setting: What have you accomplished with your weeks so far? What do you want to accomplish with them in the future?

“Both the week chart above and the life calendar are a reminder to me that this grid of empty boxes staring me in the face is mine. We tend to feel locked into whatever life we’re living, but this pallet of empty boxes can be absolutely whatever we want it to be. Everyone you know, everyone you admire, every hero in history — they did it all with that same grid of empty boxes.”

The next time you find yourself procrastinating on a particular goal or making a decision with far-off consequences, take a moment to get in touch with your Future Self:

- Write a letter from a distant Future Self — imagine what your life will be like and what things will be important to you.

- Set a deadline for your goal in terms of days, weeks, or even hours, rather than months or years.

- Visualize that deadline in the form of a “goal grid” with each box representing a day. Circle boxes for certain milestones you want to hit along the way. Write what you accomplish day by day and check the boxes off as you go.

- At the beginning of every day, imagine yourself completely satisfied at the end of the day. What one thing have you accomplished? Start on that task first.

We tend to think we’ll enjoy infinite time and opportunity in the future, but on the geologic scale of time our lives are barely a blink. Finding ways to remind ourselves of how little actually separates our Present and Future Selves may help align today’s actions with tomorrow’s goals.

3. Forget about your Future Self and use your Present Self’s love of instant gratification to your advantage.

While the two tactics above can be effective in making better long-term choices, in the end, you’re still struggling against human nature. Our brains are hard-wired for instant gratification. Instead of fighting your Present Self’s need for immediate rewards, why not use it to your advantage?

When most of us set goals, we focus on long-term results we want to see — e.g., losing weight, getting a promotion, retiring in comfort, mastering your craft, etc. While those visions of our Future Selves can be inspiring, when it comes to actually doing the day-to-day work it may be more effective reframe activities in terms of their immediate (or at least very near-term) rewards.

Take writing this article, for instance. It’s easy for me to imagine how amazing it will feel at the end of the workday to have this article done and off my to-do list for good.

Note that I did not say how amazing it will feel when the article is published to the fanfare of thousands of adoring fans and I’m offered a book deal and I turn it into a New York Times bestselling masterpiece and go on a first-class world tour to promote it, etc, etc. Instead, I’m going to focus on the sense of accomplishment I’ll feel in just four-hours time when I will no longer have to feel guilty about not finishing this thing I’ve put off for so long that it’s started to feel like a squirmy eel in the pit of my stomach every time I think about it.

(I realize that four hours from now is not exactly instant gratification in the strictest sense, but it’s a whole lot easier to care about Four Hours From Now Becky than Four Years From Now Becky.)

This isn’t just me talking anecdotally. Research partners Kaitlin Woolley of Cornell University and Ayelet Fishbach of the University of Chicago, have made a career out of studying the differences between the goals that people achieve and the ones that fall to the wayside:

“In one study, we asked people online about the goals they set at the beginning of the year. Most people set goals to achieve delayed, long-term benefits, such as career advancement, debt repayment, or improved health. We asked these individuals how enjoyable it was to pursue their goal, as well as how important their goal was. We also asked whether they were still working on their goals two months after setting them. We found that enjoyment predicted people’s goal persistence two months after setting the goal far more than how important they rated their goal to be.”

This pattern held true across a wide variety of goals from exercising to studying to eating healthier foods. For example, people ate 50% more of a healthy food when directed to focus on the good taste rather than the long-term health benefits.

These findings suggest that when it comes to achieving your goals, enjoying the process itself is more important than wanting the long-term benefits. In other words, Present Self trumps Future Self.

You can use this fact to motivate your Present Self to do (or not do) a surprising number of things:

- Instead of exercising for the bikini bod you want 6 months from now (or even the decreased chances of dying), choose a type of workout that you actually enjoy and focus on the immediate boost in mood and stress relief you get from it.

- Instead of studying hard to get good grades, choose subjects you enjoy learning about and focus on the satisfaction you get from the learning process itself.

- Instead of sending out a bunch of cold emails to hit your annual, or even monthly, sales goals, focus on how good it will feel to shut your computer and leave work at the end of the day free of the guilt that you should have done more. Or even gamify your productivity with the paper clip strategy.

And when you do have to do unavoidably boring and unpleasant tasks, try to bundle them with things you enjoy — like going to your favorite coffee shop, listening to your favorite podcast, or eating your favorite snack.

Who says instant gratification has to be a bad thing? By all means, set ambitious long-term goals for your Future Self, but when it comes to actually following through day-to-day, make sure your Present Self knows what’s in it for her too.

Homework for Present You

Now that you’ve procrastinated from doing whatever it is you were supposed to be doing by reading this article, it’s time to actually put these insights into action:

- What one goal will be most important to you in 20 years? If it’s helpful to you, write a letter from your Future Self. Write down your goal somewhere you’ll see it every day. If you’re a Todoist user, create a new project for your goal and favorite it so it shows up at the top of your list.

- List out the concrete actions that you’ll have to do to reach that goal. For example, if the goal is to write a book, you might want to set a specific daily word count you want to reach. Add that task or tasks to your project. Give each one a due date if you’ll only need to do it once or a recurring due date if it’s something you’ll need to do daily or weekly.

- Now, list out all of the things that your Present Self will want to do instead of reaching that word count. Going on Facebook, doing the laundry, answering email, etc. For each item on this list, come up with a strategy that will make it harder e.g., block (or better yet, quit) Facebook, work from a coworking space or coffee shop, block out specific time later in the day to answer all your emails.

- Next, list out any and all tactics you can think of to either automate those actions or make as easy as possible to get started on them first thing in the morning. Start building these tactics into your end-of-the-workday routine. Add them as recurring tasks — e.g., “every weekday at 5pm” — in your Todoist so you don’t forget to do them.

- Commit to a deadline for your goal — the more public and binding the commitment the better. Ask yourself how you can set a deadline in a way that will have real consequences if you don’t meet it?

- Calculate the number of workdays — or even work hours — you have until your deadline. Bold and underline this number. Write it on a post-it note and stick it somewhere you’ll see all the time and update the number regularly. Or visualize it in a grid with each box representing a day or hour until you have to reach your goal. Tick off the boxes as you go.

- Finally, list out all of the immediate rewards you’ll get from the day-to-day actions you’ll need to take to reach your long-term goal. Are there ways to make those actions more enjoyable in and of themselves? Focus on enjoying the process rather than the long-term benefits.

I’m sorry I couldn’t provide an easy answer to our procrastination problem. Our decisions about how to spend our time, what we eat, how much we exercise, where we spend our money are complex. We won’t ever do the “right thing" 100% of the time. But understanding our present bias at the expense of the future can help us start bridging the gap between who we are and who we want to become.